(I do make an exception for the elaborate Guardian hoax about The Island of San Seriffe in 1977. It was shaped like a semi-colon and its capital was Bodoni.)

No; although my posting day is 1st of every month and once in twelve it will land on the dreaded day, this is a serious post and indeed a review of a fascinating book.

For the possible inventor of the handkerchief was none other than the English King Richard, the second of that name. His tailor, Walter Rauf, describes "small pieces [of linen] made for giving to the lord king to carry in his hand for wiping and cleaning his nose.'

For this fascinating fact I am indebted to Kathryn Warner, author of a new biography Richard ll: A True King's Fall (Amberley Publishing). It is of a piece with what we already knew of him. He was a fastidious, elegant man, much given to spending exorbitant sums on clothing and personal adornment for himself and his queen.

His was also the first known commissioned portrait of an English king. So we have a slightly better notion of what he looked like than can be gleaned from earlier kings' depiction in illuminated manuscripts or funerary effigies.

You can't see the handkerchief but he probably did have one tucked away somewhere in those gorgeous robes, his hands being occupied with orb and sceptre.

I have been interested in this particular king since I first read Shakespeare's play. I think this was when I was still a teenager because Henry lV Part One was a set text for O level and I developed early the habit of "reading round the text." I didn't understand what was going on in the opening scene in which it looks as if there is going to be a joust between Henry Bolingbroke and Sir Thomas Mowbray but then the king steps in and stops it.

I didn't know who Aumerle was but thought he had a very romantic name. And I thought Bushey, Bagot and Green sounded like a trio of stage villains. What I loved was the language. Not so much John of Gaunt's "This royal of throne of kings ..." speech, which had been done to death by singing Parry's setting in the choir, but Richard's "Let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the deaths of kings."

I loved it all - even the gardener - "Go, bind thou up yon dangling apricocks."

But it was only in 2007/8 when the RSC put on the full cycle of Shakespeare's History plays that I got so involved with them.

I saw each play individually and then the whole sequence again in what was called The Glorious Moment, although it was in truth a full weekend from Thursday to Sunday. It was this that fired my interest in the Plantagenets.

"Our" Richard ll was Jonathan Slinger (who also in the rest of the cycle played Richard lll, Fluellen and the Bastard of Orléans). He gave us an epicene, arrogant and ultimately fragile king, incredulous that his people could turn against him.

Kathryn Warner gives a fully rounded picture of the monarch too and reminds us of much that shaped his character. His father, Edward of Woodstock (not known as the Black Prince till two hundred years later), was the oldest of Edward lll's many sons and the recognised heir to the throne. But campaigning in France turned him into an invalid and the heir died before the king.

Then Richard had an older brother, another Edward, who, if he had lived, would have been King Edward lV and changed the course of history. But little Edward of Angouleme died before he was five. Richard's mother Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent, had what was regarded even then as a rather colourful marital history. She was, while still a teenager, married to two men at once, had five children with the one deemed to be her legal spouse, then married the Prince of Wales within nine months of her husband's death. She was still only thirty-three.

But it meant that when Richard ll was crowned at the age of ten, he had the following disadvantages: he wasn't the son of the previous king; he was a minor and his mother had a scandalous past, leaving him open later to rumours of illegitimacy.

At the time of his coronation, Richard had three living uncles: John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, Edward of Langley, Duke of York and Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester (all named after their birthplaces, Gaunt equalling Ghent). John of Gaunt had a good claim, being the first living (though third-born) son of the dead King Edward but he didn't pursue it - something he might later have regretted.

When he was fifteen, Richard married Anne of Bohemia, who was a few months older than him. If you think of him as an effeminate king with "favourites" or lovers like the Earl of Oxford, it might surprise you to know that it was a very happy marriage. The teenaged Richard doted on his young bride and took her everywhere with him.

It was imperative for Richard to produce some heirs but sadly there were no children from this marriage and Anne died at the age of twenty-eight. Meanwhile, Henry Bolingbroke, son of John of Gaunt, was busy producing four sons and two daughters with his wife Mary de Bohun. How galling must that have been?

The having of legitimate male heirs has coloured the history of England's kings. Too few, as with Henry Vlll, and it dominates their reign and causes problems after death. None, like Queen Elizabeth the First and the outcome is the same. Too many, however, like Edward lll and you get the Cousins War (or Wars of the Roses).

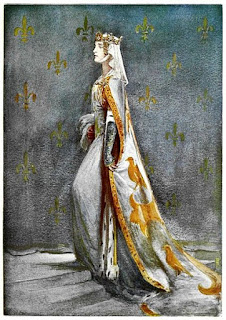

Richard was reluctant to name an heir but eventually chose his cousin Edward, the son of his uncle the Duke of York, who later held the title Aumerle (=Albemarle). Richard took a second wife, Isabella of Valois, but she was just a child, only nine when her husband was deposed. There is every evidence that he treated her kindly and was fond of her but she is not the adult beloved of Shakespeare's play, who seems more modelled on Anne of Bohemia.

The play deals with the last year of the king's reign, with Richard's sending his dangerous and fertile cousin into exile and later seizing his lands and property when old John of Gaunt dies. From then on it is inevitable that Henry Bolingbroke will return from exile to claim first his title and rights but then move on to seize the crown.

All of this is covered in Kathryn Warner's excellent biography, along with what is now called the People's revolt of 1381, which was Richard's first test of kingship, his troubles with his uncles and the Lords Apellant, his conflcts in Scotland and Ireland and the uneasy peace with France.

As well as the handkerchief story, there is a the sad anecdote about Richard's dog, who deserted him for the usurper, Henry Bolingbroke. It was "a greyhound of wonderful nature," who had belonged to Richard's half-brother. It then lived alongside the king for two years but when Richard left South Wales, the dog ran away for a hundred miles to Bolingbroke's camp at Shrewsbury Abbey and sat in front of him "with a look of the purest pleasure on its face." Henry took this as a good omen and adopted the dog, letting him sleep on his bed.

(History doesn't relate how Henry knew it was the king's hound).

Maybe this is the source (The Chronicle of Adam Usk 1377-1421) of the touching scene at the end of Shakespeare's play when Richard asks a groom which horse the usurper-king Henry rode in triumph and was told it was his own roan Barbary. Richard exclaims:

"So proud that Bolingbroke was on his back!

That jade hath eat bread from my royal hand;

This hand hath made him proud with clapping him.

Would he not stumble? would he not fall down,

Since pride must have a fall, and break the neck

Of that proud man that did usurp his back?"

Apart from some passages which are inevitably studded with names and genealogical details as a Christmas pudding is with dried fruit, Warner's is a very readable and engagingly written book. It gives you a real sense of the contradictory personality of this capable but ineffective, loyal but vengeful, generous but greedy and ultimately flawed king.

|

| Kathryn Warner |

2 comments:

That sounds fascinating.

(I'm also envious of you having seen that RSC cycle - I managed to see all 4 of the ones they did recently, (Richard II + Henry IV and V) with David Tennant as Richard II and Alex Hassell as Henry V, although it took several months to see them all!

I shall have to look out for Kathryn Warner's book.

Very interesting and the book sounds fascinating. I heard of Richard first through reading The Gentle Falcon; anyone remember who wrote it? Hilda Lewis? It was about little Isabella. I think she died young, didn’t she?

Post a Comment